Pale & Interesting

on show as part of:

Pinpoint: Banyule Contemporary Art Fair

curated by Claire Watson

Hatch Contemporary Art Space

11 November - 13 December 2014

Opposites - and how they attract

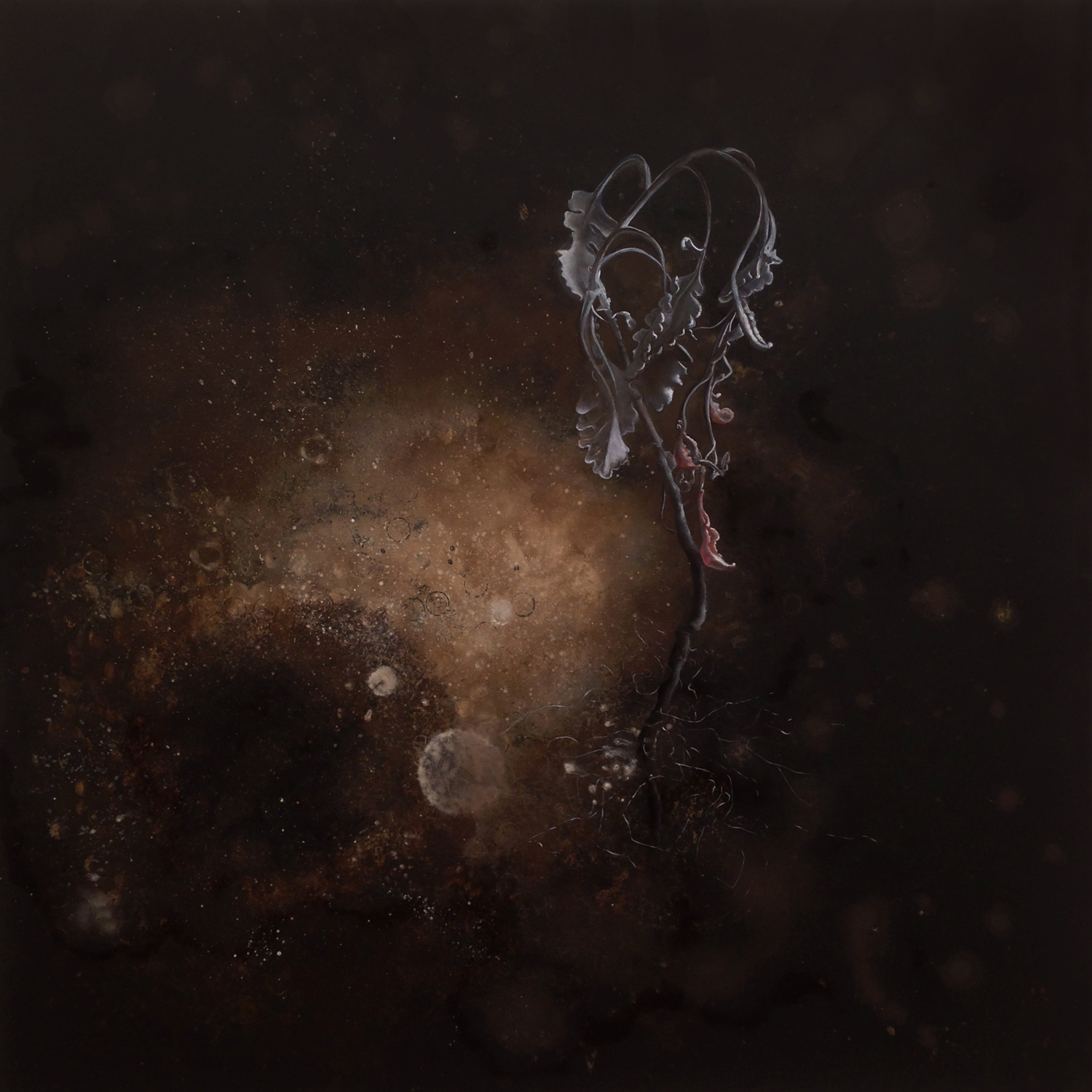

Although disparate, these paintings are my imaginary field notes about transplanted life: where nature meets culture and where a particular detail stands out from an indistinct whole.

Untouched, nature is often thought to have its own harmony and balance, not static but self regulating. James Lovelock called it Gaia, also using the biological term homeostasis which describes the way in which a system maintains internal stability.

People on the other hand have culture which can also evolve, but is just as likely to develop in great erratic leaps or seemingly random meanderings. People also seem unable to resist the urge to change and improve. We lob foreign elements into nature. We build new structures and introduce plants and animals from elsewhere that the local environment must absorb.

Not that I seek to make a sharp division between nature and culture, it's actually more interesting to look where these two meet: where they rub up against each other and vibrate.

The other point of contrast here is between white and black.

The Italians invented chiaroscuro - light/dark - to highlight matters of importance and to create drama in paint.

In painting white 'pops' - it is attention seeking. And in nature nothing stands out like a white thing. In gardens even red and pink flowers blend more chromatically with the background greens than do the white ones; and in the muted Australian landscape of my home, white stands out all the more.

But chiaroscuro also translates to clear/obscure. My use of white against dark backgrounds draws attention to the elements that are out of place but also asks about what is missing.

White is an unearthly colour according to one colour theory, or an ethereal absence of colour according to another. So although stark, these plants, animals and decorated rocks are also ghost-like, suggesting impermanence.

Darkness too is important and not just as a foil for white.

In Iceland, in the perpetual daylight of summer, the American writer Rebecca Solnit came to appreciate, as she missed it, the importance of darkness. “The sensuality of night had never been so clear to me...

In darkness things merge, which might be how passion becomes love and how making love begets progeny of all natures and forms. Merging is dangerous, at least to the boundaries and definition of the self. Darkness is generative, and generation, biological and artistic both, requires this amorous engagement with the unknown, this entry into the realm where you do not quite know what you are doing and what will happen next. Creation is always in the dark because you can only do the work of making by not quite knowing what you’re doing, by walking into darkness, not staying in the light. Ideas emerge from the edges and shadows to arrive in the light, and though that’s where they may be seen by others, that’s not where they’re born. 1

Both standing out and merging - that's what I'm attempting here. And that's what we do in life a lot of the time. We differentiate ourself yet want to be part of a group. We elevate our personal or our species' needs yet ultimately our dependance on, and 'oneness' with nature is a simple matter of life and death.

We link ourselves to nature when we talk of our 'roots' - usually describing the place we spent our childhood. But our sense of place is largely psychological, real at a personal level but nonetheless intangible. The place itself bears our scars and suffers our uses but continues to exist long before and long after our inhabitation and our imaginings.

If our sense of place is not reciprocated there is comfort, I think, in knowing that the very atoms in our bodies are part of a timeless process. That we came from stars and will ultimately feed new life when our bodies join the earth.

_______________________________

1. Rebecca Solnit The Faraway Nearby, Granta, 2013, pp.184-5