On Natives & Exotics

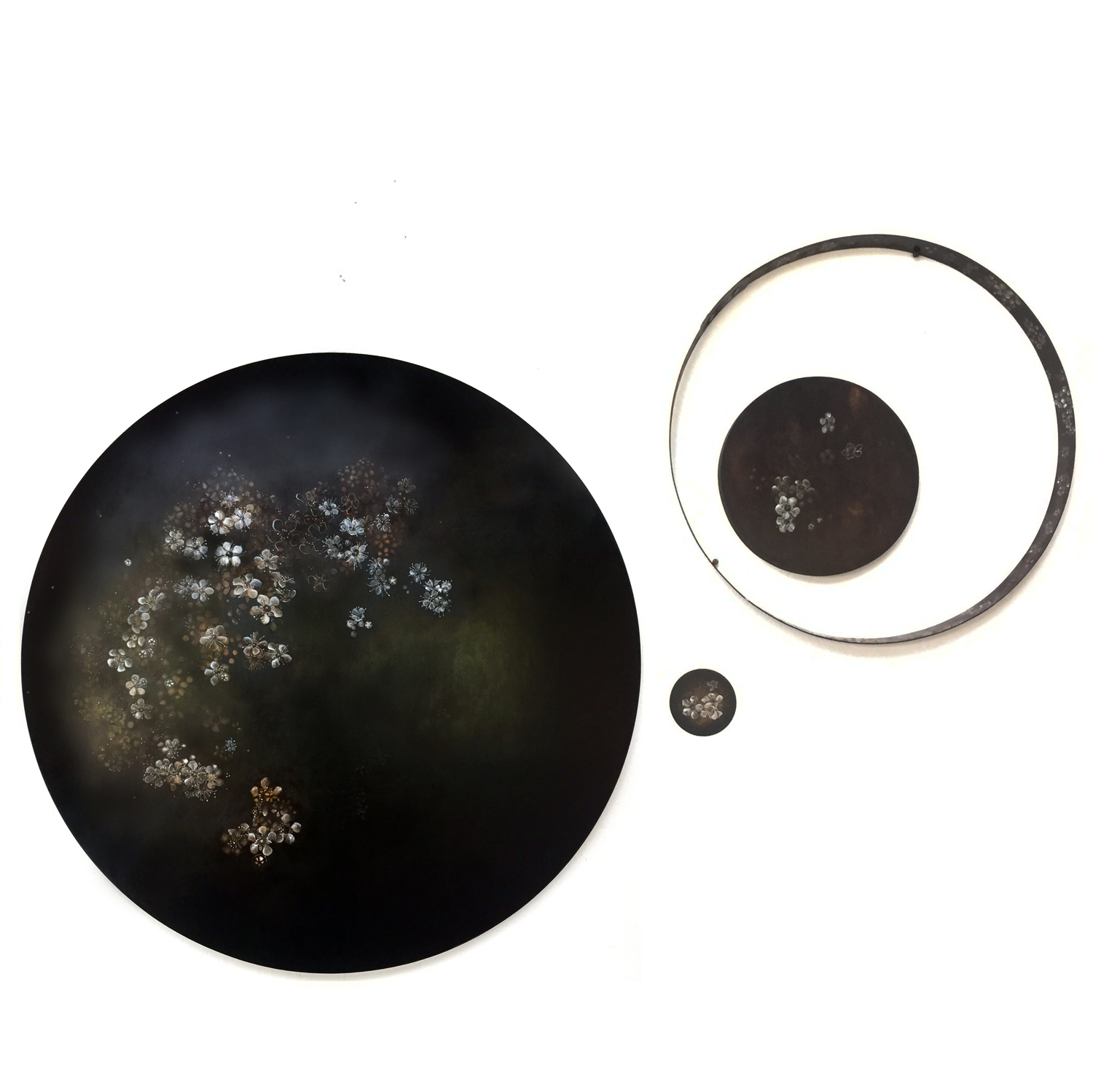

Penelope Aitken, Polypetalous pentamerous, 2019, (detail), oil, plant ink and wax on board 90 cm dia. Finalist, Bayside Acquisitive Art Prize 2019

As April 202o approaches, I’m dwelling on the ways Australians might mark the 250th anniversary of Cook's Endeavour voyage to the east coast of Australia.

Like many people I have ambivalent feelings about this anniversary and am concerned that even today, children are taught that Captain James Cook ‘discovered’ Australia.

The persistence of this myth is very frustrating. It eclipses the barely discussed contacts made by Chinese, Macassan and previous European explorers. But most especially, the salience of the 1770 story diminishes the truely awesome human history of this land - the complete and continuous occupation by hundreds of distinct first nations societies for over 60,000 years.

Nevertheless, Cook’s voyage remains interesting in itself. While most early exploration aimed to capture new territory, the Endeavour was initially funded for scientific rather than land claim discovery. A huge part of the expedition was supported by Joseph Banks, who, with Daniel Solander, Sydney Parkinson and others, gathered and drew thousands of Pacific and antipodean plants between 1768 and 1770. This party of botanists is especially interesting to me because Solander was taught by Carl Linnaeus and was one of the ‘apostles’ encouraged by Linnaeus to teach his formal binomial naming system, still used today.

It is intriguing to imagine Banks and Solander’s attempts to fit thousands of strange new plants into their European botanical schema. And important to reflect too on the ways in which systems of knowledge follow power and prestige.

At the same time folk names for plants persist alongside their binomial names and folk uses still sit behind hard science.

Moreover, well… all this naming business is pretty irrelevant from the perspective of the plants.

So right now I'm deep into some work about ‘natives’ and ‘exotics’.

‘Tea-tree’ flowers feature in much of this work, primarily for their mistaken identities. Legend has it, Captain Cook's sailors attempted to use varieties of Leptospermum, Kunzea and Melaleuca plants as tea substitutes during their first south seas voyage. The tea wasn’t so great but the hopeful name persisted for a broad range of slightly similar Australian and NZ plants. The tea-tree flowers in these paintings carry symbolic layered stories of wishful misappropriation, then all that followed from those first erroneous encounters.

In other works, layers of tea-tree, almond, plum and other five petaled blossoms jostle for precedence on solemn walnut backgrounds.

The flowers in this work can’t quite be pinned down. Some are painted in detail; some mere outlines and others are fading fast.

Originally, they were ten or more species of ‘tea’ tree flowers, from the genera: Leptospermum and Kunzea. For millennia they might have been known as Burgan, Woolerp, Nowart, Kānuka, Mānuka and more. Needless to say, the plants themselves don’t speak in English, Latin, Māori, Gunai or Woiwurrung. They communicate in the non-verbal language of flowers: chemical, optical, silent and sweet.

The actual flowers depicted have perished now. Some ended up in my dye pot and are part of the colour sitting on the surface. Others dropped from their plants and, depending on the weather, might yet float upon the breeze or be midway through worms. Eventually their atomic mush will seep into other beings through the great cycle of compost, flourishing and death that is life.